As seen in Ethanol Producer Magazine: While some ethanol plants are struggling to cover their operating expenses, Connie Lindstrom, senior biofuels analyst with Christianson CPAs & Consultants, says there is also reason for optimism in the industry. “There are plants that are hanging in there and they’re doing fine,” she says.

Lindstrom presented Christianson’s industry benchmarking numbers at the 2019 Fuel Ethanol Workshop & Expo in June and says the data doesn’t point to a specific factor for plants’ success or failure, such as size or location. “We have solidly performing plants that are any size or that are in many locations,” she says. “There are ways to be successful, even in times like this where the margins are so tight. I think just having an awareness of that is something that’s important for plants to keep in mind.”

Fundamentally, planning is key for plants, she says. “The plants that seem to be doing the best are the ones that have been making regular reinvestments in their plant and some regular conversation about the future of the facility and their organization,” she says. “The plants that were thinking about what things might be like in 2018 in 2014, when they had money to reinvest, those are the plants that are in that leader category now.”

Another factor in many plants’ success is the experience of upper management. “Many of these plants have extremely experienced leadership teams that understand what needs to be done to optimize the performance at a facility, and hanging on to those people and listening to them and making a plan going forward is the most important thing they can do,” she says.

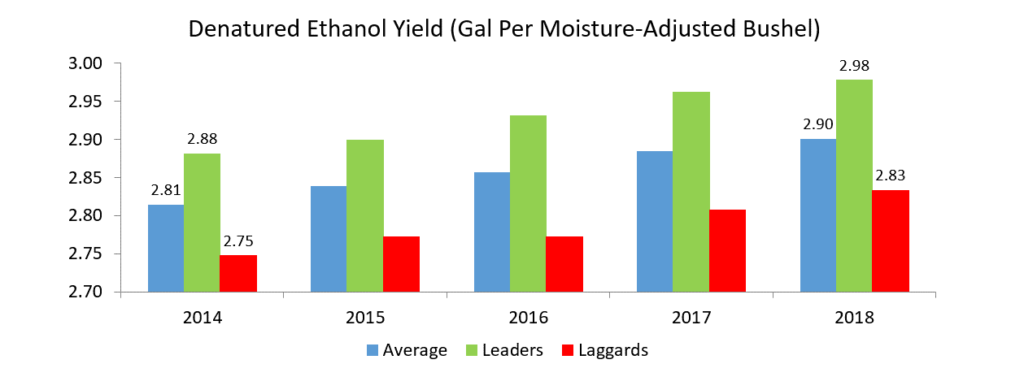

Lindstrom notes another reason for optimism is the amount of value plants have been able to extract from corn in recent years. She says increased corn oil and ethanol yields are consistent across the industry, and allow plants to lower their carbon intensity scores, while boosting efficiency. “The more energy you can get out of the same bushel of corn, the lower the carbon intensity is for those products,” she says.

That’s an advantage as more plants look to sell into California for its Low Carbon Fuel Standard, or prepare for similar programs in other areas of the country, Lindstrom says. “As it becomes clear that other areas will probably develop some kind of carbon-impact scoring for their products and that that will probably also add value, it’s something that’s becoming more and more feasible for everybody to think about.”

Risky Business

Apart from seeking new market opportunities and considering the costs associated with efficiency gains, plants can also take steps to manage their risk, according to Chip Whalen, vice president of education and research at Commodity & Ingredient Hedging. Considering input costs and forward contracts for ethanol can help hedge against the uncertainty in the corn market, he says.

“We have futures contracts that are listed out for several months, years, on corn as well as natural gas and at least several months into the future on ethanol as well,” Whalen says. “If we can identify what we would call a positive crush margin, or that difference between the revenue value on the one hand and the input cost on the other, go ahead and protect that as a single unit of risk.”

But with the current markets, maintaining a positive crush margin can be difficult, if not impossible. So, Whalen says, it becomes important to look at individual risk factors, such as the price of corn. He says a strategy he encourages is creating a diverse portfolio of contract options. “Maybe I’m laying off some of the risk by trying to have those increased forward commitments with the grower in the cash market, or trying to lay off another piece of the risk by using futures and options or using basis contracts and kind of spreading the risk across a number of different strategies or contracting alternatives.”

Those alternatives could be futures, forward contracts, options, or other alternatives. With uncertainty from weather conditions and ongoing trade negotiations in the current market, managing that risk is a difficult prospect. This year’s corn crop is a significant contributing factor.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s July Crop Progress and Condition report for corn (the most recent available at press time) showed 2019’s crop condition was at its lowest since before 2015. As of July 7, 98 percent of the corn crop had emerged in the 18 largest corn-producing states. But only 8 percent was silking. The average for silking for the 2014-2018 crop years is 22 percent. Seventy-five percent of the crop was rated good or excellent.

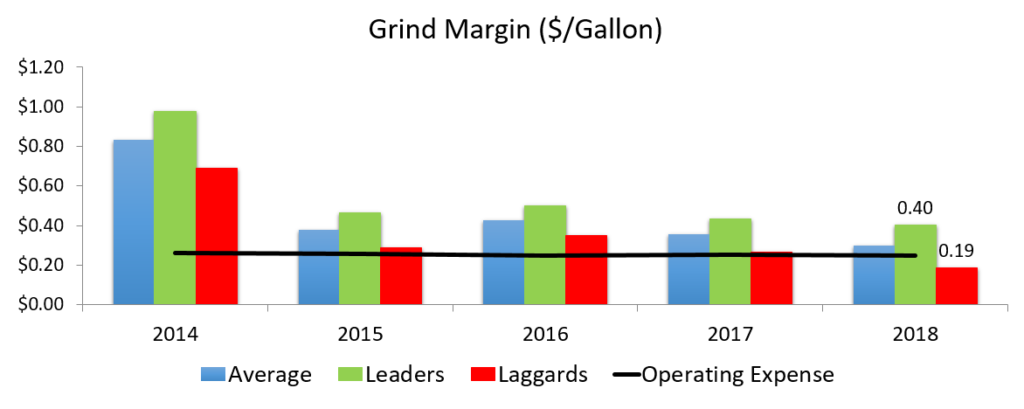

While this year’s corn crop might provide challenges, Whalen says the trend in the past several years has been declining margins. “Since 2014, the margins have been much more compressed, and it’s been more difficult, and I think this may be a function of the industry maturing,” he says. “I think plants might have to be a little more proactive in trying to manage those forward margins. So, for example, historically a 30- or 40-cent margin might have been really, really strong. Now it’s maybe more of a 15- or 20-cent margin.”

With conditions like those, Whalen says, it becomes more important for plants to manage both their input costs and the prices they get for their ethanol and coproducts.

Standing Out Through Evolution

Nick Lurty, principal consultant at n2 Solutions, says the ethanol industry won’t see a return to the higher margins that were common before 2014. “I often hear and read about margin cycles within the ethanol industry,” he says. “Our view is we are in a margin trajectory—a well-trodden path toward commoditization where tight, smart markets favor vertical economy of scale. This trajectory will transform a disparate, unorthodox competitive structure characterized by many singular, independent producers with broad EBITDA performance to a more traditional, consolidated competitive structure composed exclusively of top quartile EBITDA performers.”

To stay viable in a maturing industry, Lurty says the first step is to maintain operational effectiveness (OE). “OE determines today’s profit and foundational-to-financial performance leadership,” he says. “Sustainability favors the lowest-cost producer for profitability and resiliency against volatility. Prior to expanding or seeking other value creation mechanisms, OE squeezes every bit of value from existing assets promoting capital efficiency. Thus, OE must be a first priority, core competency in your organization.”

While being an efficient and low-cost producer through optimizing OE is key, it alone isn’t enough for ethanol plants to be sustainable. The cost advantages gained through OE are temporary and eventually reach a point of diminishing returns. Lurty says plants, particularly smaller plants, need to differentiate themselves in order to remain sustainable.

And, he says, the way to do that is to move from ethanol plants to biorefineries and offer products for different markets. Sugar production for biotechnology is one of those markets. “The most expensive aspect of biotechnology, I don’t care what market you’re in, is the substrate cost, the sugar cost.” And because ethanol producers can produce a low-cost sugar, Lurty says they should leverage that strength, combined with the capability of bioengineered organisms, to produce a variety of products.

“That’s a core competency, that’s a competitive advantage for the industry and it is technology, and so we want to leverage that ability and there’s certainly a lot more dialogue in sugars,” Lurty says.

But the sugar market is just one example. Lurty says n2’s goal is to help plants create an innovation plan, which he says starts with planning for the future. Whether that innovation includes entering a new market or investing in a new technology, Lurty says the decision-making process needs to be sound. “When we talk to clients, we see that there seems to be a gray area in explaining that process of decision-making—the investigation process, what other things they investigated and why they chose that one over an alternative investment. I think that’s what we’re trying to pitch here. Not going out there and inventing a mouse trap for yourself, but structuring your decision-making process for the next technology.”

The Costs of Efficiency

As plants seek to make their operations more efficient, Brittany Ferguson, (*formerly) senior associate at KCoe Isom says there are costs associated with efficiency gains that may not always be appreciated.

“Sometimes you have to think more of the qualitative versus the quantitative and where the value is really at,” she says. “For example, when you think of implementing a new technology, that’s fine if it’s going to increase your yields and you’re going see better margins and profitability. But what if your plant managers don’t want that technology, and if they don’t want it, you don’t have their buy-in, you lose employee morale, and then you start having turnover. You just added technology to increase your yields, but did you just also create a massive turnover which then is going to decrease your profitability because you’re scrambling, you’re losing skill sets.”

So, it’s important for plants to consider all consequences of implementing new technologies or processes. “It’s going to impact some sort of aspect of your company,” Ferguson says. “So make sure you have been very thoughtful and mindful and make sure you have considered all the benefits, all the costs, all the quantitative and qualitative factors.”

And that’s something Ferguson says more ethanol plants are becoming attuned to. “I think I’ve seen more ethanol plants realize the importance of what I would call value-added aspects of the business versus just going through the motions and building yield—doing things for the plant that is beneficial long-term and brings overall value to the firm,” she says. “In the last 18 months or so, while margins have been tight, plants have been forced to look at these value-added tasks, or nonvalue-added tasks and eliminate them.”

Two value-added opportunities plants have are IT audits and documentation of processes and procedures. The IT assessment is important, Ferguson says, in identifying potential weaknesses. She says several of KCoe’s ethanol plant clients have seen virus attacks in recent months. “The value that’s truly there to be able to identify those weaknesses in an anticipatory fashion or proactive fashion, versus having to be reactive,” she says.

Documenting a plant’s processes and procedures is also important in identifying potential impacts to profitability, she says. “If you start digging into all of the procedures and everything that’s going on in the business operation, then you can make sure that your operations, one, are maintaining a sense of internal control but, two, are also playing to the biggest strengths of your employees,” Ferguson says. Examples include matching employees with tasks that align with their strengths, as well as distributing workload more evenly among employees.

That plays into a large qualitative factor that can impact a plant: employee morale. She says most of the plants KCoe works with don’t have morale issues because they have good cultures. “Creating that tone at the top is critical,” she says. “We’ve got a saying here at KCoe that communication is a core business process. And what we mean by that is just communication across all levels of management, communication across the firm, the clients, it’s really about a culture of communication.”

*Some details modified as information changed.

With questions about Biofuels Benchmarking and the impact to the Ethanol industry, please contact Connie Lindstrom.

[button_1 text=”Contact%20Christianson%20Today!” text_size=”15″ text_color=”#ffffff” text_font=”Lato;google” text_letter_spacing=”1″ subtext_panel=”N” text_shadow_panel=”N” styling_width=”30″ styling_height=”20″ styling_border_color=”#ffffff” styling_border_size=”5″ styling_border_radius=”23″ styling_border_opacity=”100″ styling_gradient_start_color=”#1b335d” styling_gradient_end_color=”#1b335d” drop_shadow_panel=”N” inset_shadow_panel=”N” align=”center” href=”https://www.christiansoncpa.com/contact-us/”/]